4 min read

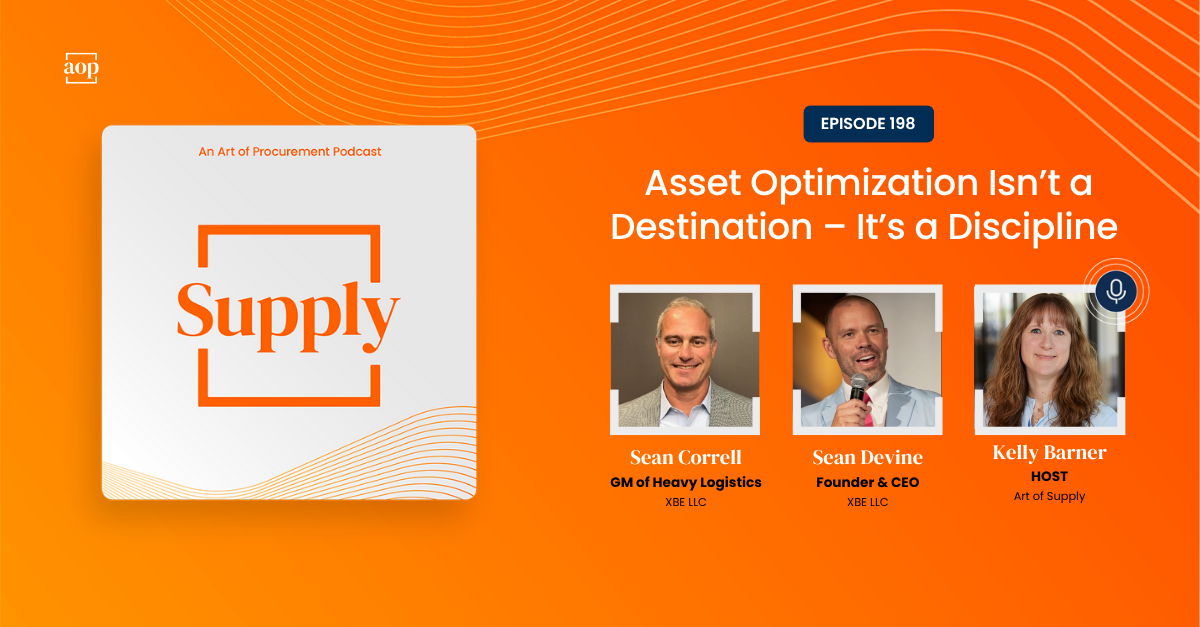

Asset Optimization Isn’t a Destination – It’s a Discipline

Kelly Barner : Updated on November 6, 2025

“No trucking company in the history of trucking companies has ever made money if their wheels aren't moving basically all the time.”

- Sean Devine, Founder and CEO, XBE

How can you get from Point A to Point B efficiently and cost effectively? That question could be applied to nearly every business and supply chain. Interestingly, the answer to the question is less important than how a team approaches it.

In this episode of Art of Supply, I had the opportunity to connect with two of my former Emptoris teammates: Sean Devine, now Founder and CEO of XBE, and Sean Correll, now their General Manager of Heavy Logistics. XBE is an operations platform focused on heavy materials, logistics, and construction.

XBE’s customers are vertically integrated companies that build and maintain roads, manufacture with concrete and asphalt, and mine and transport aggregate – expensive, asset-intensive activities. In order to operate profitably, they need to optimize owned v. hired capacity, think strategically about opportunity costs, and differentiate for the economies they compete in.

They aren’t primarily transportation companies, but logistics is a huge part of their operating costs. This creates a puzzle that constantly needs to be re-solved.

Understanding “Peaky” Demand

When it comes to owning and operating logistics equipment, companies have to monitor their asset utilization closely. Because demand for their services, and therefore their need for capacity, fluctuates, they are always trying to hit a moving target. Sean Devine describes this as “peaky” demand.

“The reason the demand is so peaky is that the distance between the origin and the destination of the materials is moving,” Sean Devine explained. “Asphalt paving in particular would have this problem, because the places that you're paving are moving around the city and around the state, and your plants and quarries are staying fixed.”

While it is possible to see this as just a logistics or distance problem, that is more of a surface distinction. It is, in reality, a “CapEx versus procurement problem,” as Sean put it. Is it more effective to invest in the equipment needed to travel those distances and do that work, or is it better to absorb the cost of hiring someone else to do it?

The goal is for the company to own the minimum capacity that they will need consistently, and then hire additional capacity to help them meet peak demand. The alternatives to solving this optimization scenario include carrying the cost of unused equipment and finding ways outside of your core business to keep that equipment generating profits.

Just like the jobs they work, the optimal point of ownership varies based on the economy in the area in which the company operates.

“The larger the market, so let's say in Chicago or LA or New York, where you've got a really big economy, the scale of the economy allows for more specialization. More small companies are offering trucking services of the sort you want, and so the available supplier capacity is higher, and therefore the percentage that you can outsource goes up,” Sean Devine told me.

“Whereas if I ran a heavy construction company in the middle of Nebraska, the same sort of economic questions exist. In other words, there's still the problem of peaky demand. The supplier alternatives are worse because the economy is smaller, and so you end up owning a relatively larger percentage of your fleet there, because the options aren't quite sufficient to compare with the option to buy it yourself.”

Missing the Forest for the Trees

Being successful in heavy logistics requires companies to have a lot of different capabilities, especially if they want to build and defend a competitive advantage. Sean Correll explained how a company’s ability to optimize their heavy logistics fits into their overall operation.

“There are three main categories of work: the trucking part of the work, the construction part of the work, and the materials part of the work. A lot of our customers do all three of them, but very few are good at all three,” Sean Correll pointed out.

“Some of them are really good at trucking. Some of them are really good at keeping the wheels moving. Some of them are really good at producing materials, and some of them are really good at coordinating and running projects, so that's their competitive advantage. It gets back to ‘What are you good at and what can you be profitable at?’”

To answer this question, companies need data. Lots and lots of data, which – as Sean Correll shared – they likely have. But are they using it as well as they could be?

To explain, he used a classic procurement example: sourcing less-than truckload and full truckload logistics.

Before a company can bid competitively but profitably on a lane, they have to know how long it will take to get the equipment to its destination and back, and whether there is a backhaul opportunity or whether they will have to accept deadhead miles.

“When you're doing these RFPs, sometimes that gets lost in the forest,” he said.

The real advantage, Sean Devine added, is knowing the same information about your competitors. How close are their locations? How much capacity do they have in that area? The objective isn’t just to win lanes; it is to maximize profit.

“If I service that lane, because I think I have a competitive advantage in terms of minimum dead time traveled, am I losing an opportunity to service another lane? This is another concept that really needs to be well thought out when you're bidding on these lanes,” Sean Correll said. “I've got a competitive advantage in terms of distance and non-deadhead miles for that lane, but is there another lane that I could be running 10 times that's even better that I'm missing the opportunity on?”

Every business decision, whether it is to buy equipment, hire additional capacity, or bid on a lane, comes with the possibility of profit, but also a cost to serve. Striking the optimal balance – and staying focused on core business profitability – is an ongoing challenge, or opportunity, that smart teams must manage over time.

The XBE approach demonstrates that optimization isn’t a destination. It’s a discipline. Whether you’re hauling asphalt or analyzing spend, the challenge is the same: balancing ownership, opportunity, and motion. Profitability, like a well-run fleet, comes from keeping your wheels (and your thinking) constantly moving.