How could Procurement help scientists and engineers innovate and solve technical problems by enabling an external partnership at a rational cost?

It’s safe to say that regardless of the role people have in an organization, work is an unending – especially as organizations are now leaner than ever before, yet still working with constant vigor to increase productivity and grow (or survive). Add to this ever accelerating pace a myriad of distractions such as e-mail and meetings, and time to contemplate new ideas (let alone truly explore them) becomes exceedingly scarce.

From a supplier perspective, investing in new and innovative products carries risk: of development failure, of a product failure due to misunderstood markets, and the opportunity cost of not pursuing investments in competing innovation. Consumers and sales are often more focused on the dance around existing products (cost/revenue) while procurement lobbies for a place at a table from which to demonstrate its value.

This is a story about how procurement, acting as a partner to the business, can bring about the creation of innovative collaboration between internal and external interests.

BACKGROUND

In the cutting-edge cell therapy space, the overall cost of goods is highly driven by scale – just like in every other industry.

Current regulatory requirements call for the operation of sterile clean rooms, which limits the number of treatments that can go through a facility, making them expensive to operate. Technologies that produce traditional drugs have been around for decades or more, and their manufacturing processes can make thousands or more doses per production batch, therefore benefitting from economies of scale.

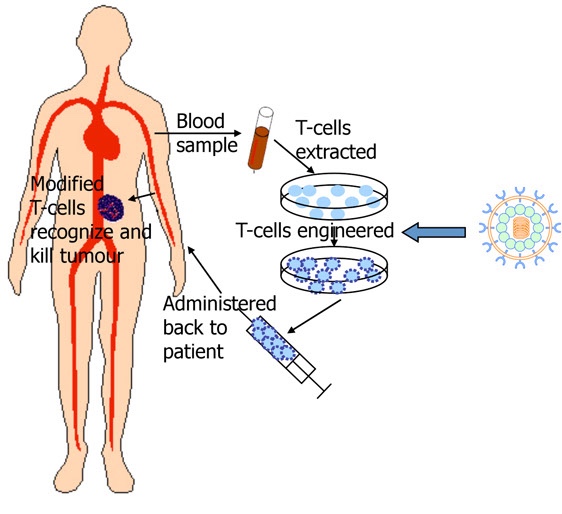

Consider that cell therapies are actually drugs that are modified living cells – yes, they are alive! One must create and maintain an environment in which the drug stays alive, thrives, and avoids any contamination from within its own little universe which would otherwise render it useless to a patient. The process is complex to say the least.

CAR T-Cell Therapy: How it Works. Source: Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

Without automation, it will be difficult to gain sufficient scale to lower the cost of cell therapies enough to make them available to large populations of patients. Despite this, cell therapies have considerable disruptive potential since many have shown the potential to actually cure cancer.

According to Seeking Alpha, total financings in gene and cell therapy companies totaled $10.8 billion in 2015, which represents a 106% increase over 2014. This level of investment represents more than many Top 10 Pharma company’s entire annual R&D budgets – astonishing capital flow for a drug that has not yet learned how to scale!

THE CHALLENGE

A cell therapy technical team had embarked on an effort to figure out how to automate their process, but did not have the internal resources and know-how to deliver the initiative quickly.

They made a strategic decision to identify a partner with the expertise and experience to develop an automation solution. As the technical team discussed their venture with potential collaborators, they received financial terms for the endeavor. When their finance team was asked to approve the funding, they insisted upon financial justification for the project.

A cycle began between the two teams, with the technical team providing a technically biased justification and the finance team requesting the financial justification. Finance kept asking for the business case and the technical team was unable to provide one – enter procurement.

With externally collaborated projects or the creation of innovative products, the price (or cost) is often determined by what the innovator (external collaborator) believes the buyer/investor will pay relative to the excitement around a product that can solve the problem.

Sometimes, this emotional judgement is exacerbated because cutting edge technology areas, such as the case with cell therapies, are flush with cash. Overpaying does not always force a choice between competing priorities.

The result is an irrational price.

How do you determine the cost of a product that does not yet exist?

Many procurement professionals approach proposal situations by acting much like the technical team did in this example, starting by asking for a price. Once receiving a price, procurement’s standard action is to seek an alternative product or service provider to create a competitive situation.

This is a simple way of utilizing market economics to determine a price.

However, how does a team determine the cost of a product that does not yet exist?

The challenge is complicated by the technical team’s deep conviction of the external partner selection, and the partner is usually aware of this conviction, which means the team is anchored by an irrational price. As a complication, in the background, finance will not approve the collaboration budget without having a clear underlying business case.

To break the impasse, procurement needed to partner with the technical team to create a business case that satisfied finance – rationalizing the cost of the collaboration.

The procurement team changed the perspective by asking: what is the innovative product’s quantitative worth to its internal customer? In this case (developing a cell therapy automation technology), procurement dug deep to understand the cost of the manufacturing process to which the new technology was applied.

THE SOLUTION

Procurement started by breaking down current process costs into its segments:

- Fixed Cost – How much did each processing room/space cost to operate per day? Procurement looked for the capital depreciation of the equipment and building assignable per cell processing activity. To do this, they worked with the technical team to discover exactly what equipment is used and with finance to understand the cost of the applicable assets, e.g. the depreciation expense finance assigns to the budget. Then they determined how many people are needed to execute the process. They were able to consider this a fixed cost as these people are usually on staff and paid without regard for the number of processes executed – but are often directly proportional to volume.

- Variable Cost – How much was paid in consumables for each process? In a cell therapy process, items cannot be reused or they would be considered capital costs. Bags, food for the cells (the Pharma jargon is ‘media’), tubing, protective equipment for personnel, etc. Utility cost (which could be fixed cost instead). Added together, these comprised the total variable cost component per treatment.

- Strategic Investments – What strategic investments would be made (such as an expansion)? What are the timelines for any applicable strategic plans? Understanding the overall strategic plan was necessary because procurement needs to account for what impact future investments/improvements may have.

- Total Potential Output – Before investing in a new technology (in this case an automation platform) procurement must capture the maximum output of the facility operating under the current process without the application of technology.

Procurement was then able to create a picture of the total investments about to be made and the minimum achievable cost per process.

Translating impact into ROI…

The next step was to determine the impact of the technology.

In the case of our cell therapy product, Procurement looked at:

- What equipment was made obsolete by the new technology? What was its total cost to write-off less its resale value? How much depreciation expense would not be realized after the equipment is no longer an accounting asset?

- Can the process be sped up using the new technology? How much less time per process step?

- Since machines can run without the need for constant human intervention (or energy) then more processes can be run simultaneously, therefore spreading out the worker’s cost over a greater number of processes.

- With automation, can the operation be run with less people?

- The proposed cost of the automation should be excluded. This is what the methodology intends to determine.

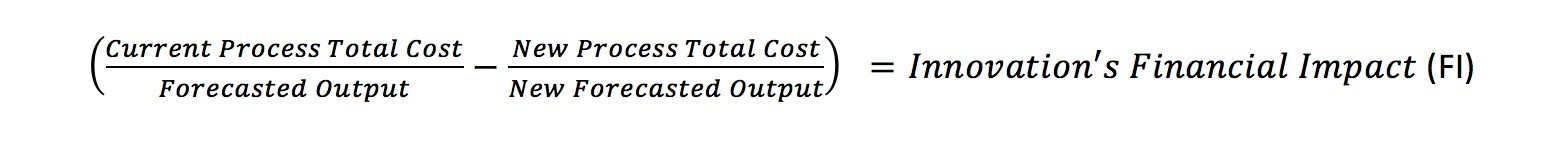

Simplified in mathematical terms, we are building a differential financial model comparing cost with and without the application of new technology:

However, this only provides a snapshot of the potential investment in a single moment in time and for a limited set of inputs.

Next, time and the impact of already planned strategic investments and improvements on future outputs need to be quantified.

Since it was known how long the current process took, the number of staff needed to run the process, and time required it was not difficult to calculate the maximum capacity of the facility using the current process over time.

Meanwhile, the commercial (sales) team had provided a forecast of not only how many potential people could benefit from the treatment, but also how many were likely to be treated.

It was apparent to the team before starting the automation collaboration journey that a facility expansion would be needed to meet demand. The facilities engineering teams had already planned the expansion. The strategic expansion plans assumed the current process (without an automation platform) was applied, also requiring more people, although some operational efficiencies and economies of scale were anticipated.

Procurement took all of these inputs and information gleaned from working closely with all of the teams (sales, engineering, technical, and finance) to create a picture over a five year period for what the holistic cost would look like utilizing the current and future (automation applied) processes.

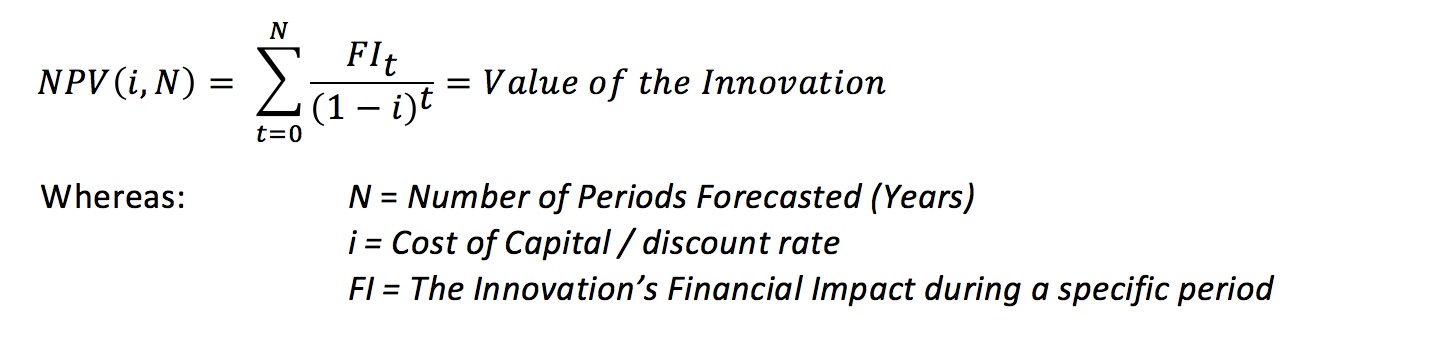

Net Present Value (NPV) methodology was applied to unify the effects over time and quantify value.

The NPV combines the result of all of the differential financial models and the “Value of the Innovation” now becomes a rational valuation of the potential collaboration.

MOVING FORWARD ON A RATIONAL BASIS

Once the math was worked out, the real fun began. In this case, since the rational value was significantly less than that the price proposed, once procurement shared the result with finance the entire collaboration quickly became jeopardized. Obviously, this also made the technical team, who were emotionally invested, less than pleased. The procurement team’s business partnering skills were then on full display (and critically needed). Procurement convinced finance that if they could support spending up to the rational value for the collaboration, procurement would negotiate to this target. Finance agreed – and the technical team remained a nervous wreck.

Time to Negotiate!

With a solid mandate to negotiate against, procurement engaged the technical team’s external partner.

The negotiation team, led by procurement, used the new rational value of the automation project as a basis to re-anchor the conversation. The negotiation team was transparent about their financial models and assumptions and explained that the cost of the collaboration would need to be reduced to fall in-line with the new rational value. Without this they could not proceed since the existing process was cheaper than the innovative one.

As with most negotiations and collaborations, there are many elements beyond price that drive each party’s interest in a deal – and this example was no exception.

The final result however, delivered an overall reduction of the deal’s contribution to the process’ variable cost by 70% and restructured in such a way as to reduce the investor’s financial exposure by 75%. As may have been guessed, both the finance and the technical teams were also happy with the result.

CONCLUSION

There is a great deal of buzz in the procurement world about delivering value beyond savings as the businesses procurement professionals support require increasingly diverse and creative contributions to create competitive advantage.

In this example, procurement applied influencing and negotiation skills to align two areas of the business who often have a difficult time communicating with one another.

In Summary: procurement can enable cutting edge innovation by acting as a facilitator between an organization’s internal innovators and external partnerships – enabling breakthroughs that otherwise may take much longer to create.

Perhaps the most powerful consequence was procurement being seen by the technical team, arguably the heart of any company’s innovative engine, as a valuable partner – opening the door to deliver more innovations, next time starting as a trusted partner instead of an outsider.

Please note: this article does not represent, be it expressed or implied, the views, opinions, policies, strategies, or other, of the Author’s employer. The Author wrote the article in his private capacity.